Burt Shavitz, a rural beekeeper whose homespun marketing for natural personal care products transformed him from an unknown recluse into the familiar scruffy face of a line of balms that healed a million lips, died on Sunday in Bangor, Me. He was 80.

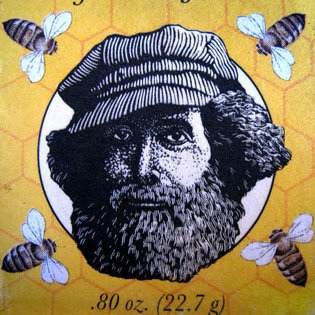

The cause was respiratory problems, said Christina Calbi, a spokeswoman for Burt’s Bees®, the company Mr. Shavitz co-founded in 1984 and which was sold to Clorox in 2007 for about $925 million. The brand still bears his bearded visage, wistful eyes and signature striped locomotive engineer’s cap.

Even after the sale, Mr. Shavitz remained a paid spokesman for Burt’s Bees, though he had returned to his hermit’s existence in a 400-square-foot converted turkey coop in Parkman, ME, northwest of Bangor. The abode was equipped with a radio and refrigerator but not a television or running hot water.

I realized I had it made because you don’t have to destroy anything to get honey. You can just use the same things over and over again, put it in a quart canning jar, and you’ve got $12.

In 1984, Mr. Shavitz picked up a 33-year-old hitchhiker, Roxanne Quimby, who became his business and romantic partner. Ms. Quimby, a former 1960s radical, first recycled his leftover beeswax into candles. Then, improving on a formula found in a 19th-century farmer’s journal, she combined the wax with sweet almond oil, and Burt’s Bees lip balm was born, in 1991.

Before long, what had been a $3,000-a-year subsistence business was transformed into a multimillion-dollar purveyor of eco-friendly lip balm, lotions and soaps packaged in school bus yellow containers.

The ingredients weren’t new, but the market for organic beauty ointments was booming. “Many of the products we produced were also produced by Cleopatra,” Mr. Shavitz said.

The ingredients weren’t new, but the market for organic beauty ointments was booming. “Many of the products we produced were also produced by Cleopatra,” Mr. Shavitz said.

The original peppermint lip balm is still the brand’s best seller.

This rural beekeeper’s roots were distinctly urban. Ingram Berg Shavitz was born in Manhattan on May 15, 1935. His father, Edward, was an actor. His mother, the former Nathalie Berg, was a sculptor and artist. He grew up in Flushing, Queens, and on Long Island, in Great Neck. He attended college in Delaware but was drafted before he finished and served in the Army in Germany. He also changed his name to Burt.

Instead of joining his grandfather’s graphic design business, he studied photography, worked part-time for Time-Life as a photojournalist and covered for various publications John F. Kennedy’s inaugural, Malcolm X and the civil rights movement, and the first Earth Day, in 1970.

That same year he accepted an arts grant in Ulster County, N.Y., and left Manhattan for good, vacating his $30-a-month apartment on Third Avenue and East 92d Street and heading north with his Volkswagen van and motorcycle.

In Ulster County he worked as a caretaker at Mohonk Mountain House and learned beekeeping as an avocation before eventually moving to Maine. He was driving his yellow Datsun pickup when he spotted Ms. Quimby, a would-be graphic artist getting by as a waitress, hitchhiking from her cabin near Lake Wassookeag in Maine to the local post office.

Their partnership endured for about a decade, ending not long after sales had reached $3 million annually and the company had moved to North Carolina, in 1994, to take advantage of lower taxes and a larger labor pool. Mr. Shavitz said he was forced out after having an affair with an employee. Ms. Quimby bought his one-third share for $130,000 (she owned the other two-thirds), but gave him $4 million more after the company was sold.

“Burt and I shared a long and unique journey through many years and probably many lifetimes together and apart,” Ms. Quimby said on Monday. “I don’t assume that his passing marks the end of that journey.”

In a 2013 documentary titled “Burt’s Buzz,” Mr. Shavitz said, “I’d like never to see her again.”

Mr. Shavitz, who died in a hospital, is survived by a brother, Carl.

Mr. Shavitz fell in love with Maine on childhood vacations.

“I’ve got 40 acres,” he told The New York Times last year. “And it’s good and sufficient and it takes good care of me. There’s no noise. There’s no children screaming. There’s no people getting up at 5 o’clock in the morning and trying to start their car and raising hell. Everybody has their own idea of what a good place to be is, and this is mine.”

He had hawks and owls and stunning sunsets and his neighbors’ good will, he explained, and no claims to gregariousness. Two of his dogs were listed by name in the local telephone directory; he wasn’t.

“A good day,” he said in the documentary, “is when no one shows up and you don’t have to go anywhere.”

Source: New York Times