August 6, 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of the dropping of the first atomic bomb on a human population, specifically the people of Hiroshima, Japan. As a commemorative series, Women Of Green is taking a look back at the impact of nuclear war on the lives of women. This is the first post in the series.

Mothers and Daughters Reflect on the Bomb

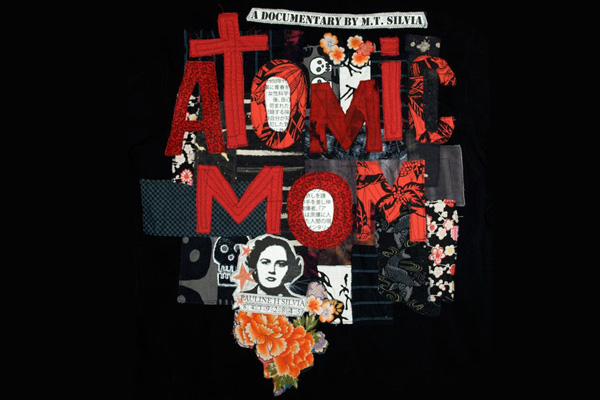

In looking at the effects of nuclear weapons on mothers and daughters, the documentary film, Atomic Mom makes clear not only the past and effects, but also a way forward. In addition, filmmaker M.T. Silva has created Momisodes, a web series of Atomic Mom where mothers and daughters share thoughts on peace, and you can contribute your own ‘momisode’ to the series.

The Film:

Two decades after the end of the Cold War, the U.S. President claimed it was a particular mission for his administration to reduce the numbers of weapons on the planet, and to secure those weapons and materials that remain.

The importance of this mission is too often forgotten in the current century—except when politicians raise the specter of scary nations who might have or attain weapons, like North Korea or Iran, or scary, non-nation groups pursuing “nukes.” What gets left out of these formulations is the very hard lessons offered by actual attacks.

Atomic Mom reminds you of these lessons in unusual and aptly disquieting terms, terms you may not have heard before. “I knew that my mother had… worked on the atom bomb,” narrates M.T. Silva. “As a child, that’s what we called it.” As a child, she goes on, she had no idea what this meant, either to “work on” the bomb or what it was. Pauline was a researcher at the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory in San Francisco (“the rad lab,” they called it), while her daughter imagined she was living out “a James Bond movie, espionage spy kind of thing.” M.T. was both mystified and proud: “My friends’ moms were, you know, making Rice Krispies treats, but my mom, she was doing secret government work, with the atom bomb.”

As a young woman, M.T. was inspired by Helen Caldicott to protest nuclear proliferation, but when she suggested during a radio interview that her mother was ashamed of what she’d done, Pauline objected. M.T. stopped speaking about her mother in public and for years, they didn’t speak with each other about her mother’s work. Atomic Mom shows how they came together, to think through the past, how her mother’s employers lied, how workers and soldiers were exposed to radiation in the desert, how the bomb continues to affect individuals and families for generations after it was detonated.

The film pokes through this past by way of interviews and newsreels and official government recordings, images of the Nevada desert, demonstrations of how to “duck and cover,” and mushroom clouds. Over a shot of a family sitting down to a picnic on a white cloth, a male narrator intones, “If you’re caught in the open and there’s a brilliant nuclear flash in the distance, take cover immediately,” at which point the family members pitch themselves forward, as if “cover” from a nuclear blast is available somewhere just off-screen.

These are the sorts of fiction that allow nuclear “research” to go on, then and now. As Pauline recalls, she was a Navy scientist, enlisted in 1952. Her daughter’s film shows a pile of white mice clambering over one another in an aquarium, as she recalls that she studied “how x numbers of mice would be irradiated with x amount of x-rays,” measuring effects. Later, they performed tests on dogs, she remembers, and a selection of handwritten notes shows lists of experiments and Pauline’s comments on which dogs had stopped eating and which had died. At the time, she was “compartmentalizing” (“They have a name for it now,” Pauline observes), dividing her life into being a single mother and a woman with an advanced degree, hired to do an important job.

All this was unusual then. “I wasn’t viewing this as a weapon, not in my personal frame of reference,” Pauline says. Now, she looks back and turns tearful. When, many years later, in 1995, she took her cats to the vet, she couldn’t bear the sound of their toenails scraping on the metal table, as it made her think of the dogs she worked on, and what she characterizes now as “such pain and agony.”

The film lays Pauline’s genuine pain alongside the trauma of another mother, Emiko Okada, who was just eight years old when the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. She and her parents were eating breakfast, she says, and they heard the plane and then saw a flash. Because her family lived on the outskirts of town, she remembers, they survived, save for her older sister. She shows paintings of the explosion and fire—red and orange—as she goes on, “Within 10 seconds, the fire that wiped out the city rushed at us full speed. Everyone was naked, their bodies were swelling up and their hair stood on end and some people were so deformed that I couldn’t tell if they were male or female.”

Such suffering was soon consigned to ore research by the U.S. government, as doctors studied the effects of radiation on victims and suppressed their results, including movie footage and photos. As these images are now available—and heartbreaking to see in this film—it’s evident that the weapons’ destruction was only a first step, that the cruelty conducted under the name of “science” was stunning.

Back in the States, Pauline was unaware of what her own work might have meant. Assigned to the Nevada Test Site and a witness to five of the 11 atomic detonations during “Operation Upshot-Knothole,” she’s burdened with memories and also the need to piece together what was deliberately obscured back then. Considering it now, with M.T., Pauline is moved to tears and also not: she won’t contemplate the possibility that her own physical maladies now might be consequences of radiation exposure back then. Emiko, with whom M.T. meets in Japan, knows exactly what caused her own daughter’s incurable blood disease.

The Future:

In looking at the effects of nuclear weapons on mothers and daughters, Atomic Mom makes clear that whether this lesson is learned, this is the legacy of all atomic parents and children going forward.

The Momisodes:

Watch the trailer, or purchase the DVD.

Website: AtomicMom.org

Momisodes Series on Youtube

Source: PopMatters.com

Women Of Green needs YOUR voice to be part of the conversation. We encourage your comments and questions below, on facebook/womenofgreen, and on twitter/womenofgreen. Say It and Share It! We’re here to Turn Up The Volume!